Perfectionism vs. Progress

Perfectionism is a terrible disease. I suffer from it as I know many others do. Especially as a flute player or musician or artist, perfectionism can be helpful or it can be detrimental. Yes, we should always strive to have all the correct notes, correct rhythms, correct dynamics, breaths, style, interpretation, vibrato, tone colors, phrasing, etc.

Can you see why perfectionism is an ongoing struggle?

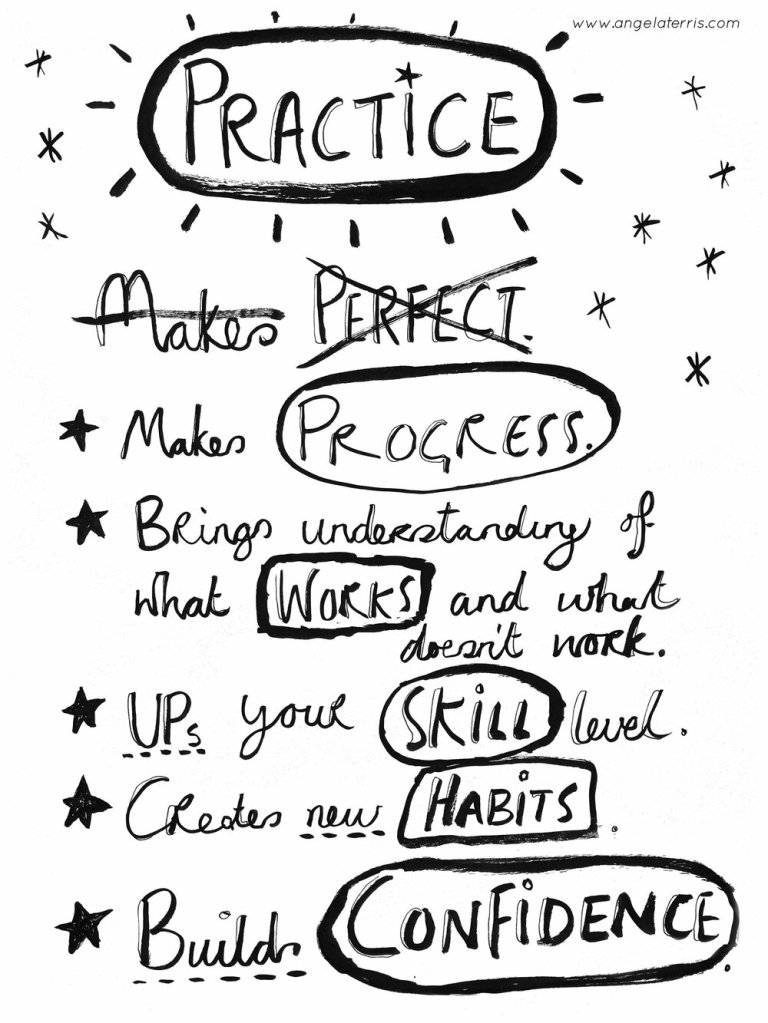

In music and in sports, you often hear the phrase Practice makes Perfect. I prefer to use the phrase Practice makes Progress. Here I thought I was so brilliant in coming up with this, but when searching for a photo to use, I found that I wasn’t as brilliant as I thought I was – haha.

The picture above says it all. If you don’t practice, you can’t expect progress.

Practicing is a developmental process to learn what methods are helpful to you. As a teacher I can attest that every student is different. What works for some doesn’t always work for others. That’s one of the things that makes teaching so fun. Finding and creating new ways to affectively teach each music student.

If you want to become a better flute player – or better at anything for that matter – you have to spend time working on that skill.

The more you practice, the better your flute playing habits will be whether those are good habits or bad habits. Hence the need for a private flute teacher to ensure you are practicing good habits.

The more you practice, the more confidence you can achieve with your tone, scales, songs and flute playing. It’s fun to really know a piece well and be confident with it, especially when preparing for a performance. That is impossible to achieve unless you are practicing smart. (That will be another post for another day.)

The main point is this: If you expect to improve as a flute player or anything else in life, you should practice consistently and regularly. That’s all there is to it.

“Practice makes Perfect Progress”.